This

car climbed Mt. Washington

Remembering the Maine-built

Stanley Steamer.

by Glenn Adams

Associated Press

Copyright © 1998 Associated Press

This story first appeared in the Portland Press

Herald on December 28, 1998.

The Stanley Museum in Kingfield

honors the enterprising twins, F.E. and F.O., and is housed in a

converted wooden high school they designed. It includes restored

Stanley Steamers and family treasures such as violins, relics from

their photographic dry-plate business and a Stanley Motor Carriage

Co. clock. The Stanley Museum in Kingfield

honors the enterprising twins, F.E. and F.O., and is housed in a

converted wooden high school they designed. It includes restored

Stanley Steamers and family treasures such as violins, relics from

their photographic dry-plate business and a Stanley Motor Carriage

Co. clock.

AP photo

|

KINGFIELD - This western Maine town may be best known for downhill

skiing, but it was an uphill climb a century ago that brought it a puff

of glory.

Sugarloaf, the state's tallest ski mountain, is in the neighboring

town. But Kingfield has its own claim to fame: It's the birthplace of

F.E. and F.O. Stanley, the identical twins who gave us the quirky

automobile named for them.

And 1999 will be an important year for aficionados.

The new year will mark the 100th anniversary of one of their early

models shaking and panting its way over a bumpy road and past sheer

dropoffs to the top of 6,293-foot Mount Washington in New Hampshire.

Owners of the remaining Stanley Steamers are gearing up to re-create

the event of Aug. 31, 1899, that marked the first horseless carriage to

climb to the top of New England's highest peak.

Nearly 600 people have been notified, and steamers are expected from

as far away as California and England.

"They are a special ilk," said the great-granddaughter of F.E., Sarah

Walker Stanley, who will bring an 1899 Locomobile to the festivities.

"They run their cars, they know the technology, they know the history."

The hubbub is also expected to draw attention to Kingfield's modest

but fascinating Stanley Museum, which is housed in a yellow-and-white

converted wooden high school that was designed by the Stanley brothers

and was later saved from demolition by town fathers.

The Georgian structure is home to a few restored Stanley Steamers and

a growing collection of family treasures.

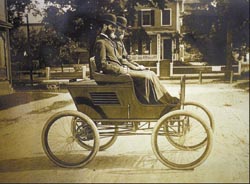

At right: Kingfield natives F.E. and F.O. Stanley show an early

Stanley Steamer. AP photo

There are finished and unfinished violins the twins built, pictures

made with an airbrush F.E. invented, relics from their photographic

dry-plate business and a clock from the Stanley Motor Carriage Co.

A recent addition to the museum is an early buggy-styled wooden

Locomobile equipped with a steering "tiller," white tires and, most

curiously, a socket to hold a horsewhip.

The museum is a monument to an age of bare-knuckled capitalism and

engineering creativity that ushered in modern America, as presented by

the Stanleys, Edisons and Wrights of the day.

Francis Edgar Stanley and Freelan Oscar Stanley, the second and third

of six siblings, showed unusual intelligence and ambition early.

F.E., an award-winning portrait artist, patented the airbrush in

1876. The brothers became partners in the Stanley Dry Plate Co. in 1884

and patented a dry-plate coating machine that revolutionized the

process.

Eastman Kodak bought the Stanleys' dry-plate company in 1904, long

after F.E. had begun tinkering with motorized carriages, using steam as

the energy source. His wife's inability to ride a bicycle was said to

have spurred him on.

F.E.'s machine was demonstrated in 1898 at Charles River Park

Velodrome in Cambridge, Mass., where it set a world record of 27 mph.

The brothers worked in a converted bicycle shop in Watertown, Mass.,

filling 100 orders in 1898-99 before selling out to a magazine publisher

who rechristened the early Stanley Steamers the Locomobile. Later, they

went back into the business.

By the time the Stanley Steamer hissed into the sunset in 1924,

around 11,000 of them had been built.

In addition to being innovators, the brothers were skilled marketers.

F.O. took center stage in the 1899 publicity stunt in which he and his

wife Flora drove the chugging steamer to Mount Washington's summit.

Later, he gave President William McKinley the first ride a president had

ever received in a motorized carriage.

Powerful, speedy and exquisitely simple, the Steamers were powered by

pressure built up in a 23-inch, piano wire-wrapped boiler that drove

pistons in much the same fashion as a locomotive engine.

There was no transmission, and it used water instead of gasoline. But

that's where practicality ended.

The removal of roadside water troughs in 1914 because of an epidemic

of hoof-and-mouth disease is cited as one reason for the demise of the

Steamer, whose thirst needed to be slaked regularly.

The steam-powered carriage business ran out of steam six years after

F.E. was killed when he crashed a steamer in 1918. F.O. turned his

attention to a violin-making business before his death in 1940 in Estes

Park, Colo., site of a hotel he built and another Stanley Steamer

museum. The Steamers were known for their "coffin nose" appearance, and

early models required some level of expertise to manage all of the

valves and knobs to keep them chugging smoothly.

Later models were more refined. And some were even luxurious: A 1916

touring car gracing the Kingfield museum is a deep, midnight blue, with

soft top and leather interior. Although they have been relegated to the

oddball file of automotive relics, m Many Steamers remain operable.

However, Sara Walker Stanley said the steam-powered carriage that she

and her husband are towing from Chatham, N.J., won't be headed up the

windy road to the top of Mount Washington.

"It just doesn't have it any more," she said. "For this century-old

car, it would be the end."

Have a question or comment? Send e-mail to wheels@mainetoday.com.